WHAT IS MADE-TO-MEASURE AND WHY DID IT GO OUT OF FASHION… OR DID IT REALLY?

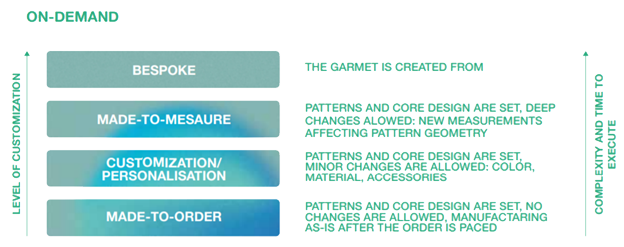

Bespoke, made-to-measure or customization/personalization, and made-to-order represent very similar concepts. They could be grouped under “on-demand” and are frequently used interchangeably (vocabulary at the end of the chapter) with a major difference being the depth of customization.

Bespoke is a high-end, hand-made service based on the customers’ measurements, usually requiring two fittings and rework/adjustments by the tailor at the end. Made-to-measure is not hand-made but still manufactured specifically for the client based on the customer’s measurements, just by the factory and not the tailor.

Made-to-Order with Customization allows the customer to choose from several pre-set options, for example, your collar shape and colour.

Made-to-Order/ pre-order implies that the model is fully developed and will be manufactured post order placement as-is, without customization or personalization.

Since the dawn of fashion, these concepts have been around – the customer enters the atelier, orders a garment, selects the fabric, gets his/her measurements taken, and comes back when the garment is ready. In all the concepts mentioned above, demand comes first and determines the quantity of the final product.

While representing a sustainable approach to clothing manufacturing, on-demand fashion was slowly overshadowed by ready-to-wear sometime before WW2 and was later almost replaced by fast fashion, bringing along standard sizing, assembly lines, and processes automation.

Why was this sustainable approach replaced? Let’s take a look at the historical developments that ultimately caused on-demabd to fall out of fashion.

Until the early 19th century, new clothes were made by local seamstresses or by women within the household. It wasn’t until the 1850s in Paris, when Charles Frederick Worth, a British fashion designer, started designing and selling bespoke dresses under his name. This set a precedent and was marked as the beginning of the haute couture industry as we know it today. Around the same time, across the Atlantic, an American inventor Elias Howe received a patent for the lockstitch sewing machine. This invention revolutionized factory and in-house garment manufacturing.

One area where it was first used was the mass production of military uniforms by the US government, which became the de facto first ready-to-wear garments in history. Even pre-war, ready-to-wear sales had reached unprecedented levels around the 1920s, spurred by rising incomes, easy credit, and the increasing social acceptability of spending money on consumer goods that were not absolute necessities.[1] To accelerate the supply, near the end of the Great Depression the Roosevelt Administration created a project to standardize women’s measurements: from July 1939 – June 1940, American women were measured to formulate average sizing. This resulted in savings on alterations and increased the sales of ready-to-wear apparel.[2] Ironically, even though the sizes were created to simplify and standardize on a mass scale, nowadays, fit remains the number one return reason when shopping online.

Scarcity of raw materials and economic hardship only made ready-to-wear cheaper and more attractive alternatives to made-to-measure, especially in war-torn nations. For example, heavy cloth supply cuts during and post WWII brought clothing and raw materials rationing practices to the European general population and clothing manufacturers. As a result, the garment had to be produced as cheaply as possible to bring higher margins. This also affected the style of clothes — they became more utilitarian and functional.

In Britain, a government-run scheme known as Civilian Clothing Order 1941 (CC41) was introduced to make clothes affordable for the working-class, requiring strict design standardization and almost uniform-like garments. To develop the most efficient clothing models and comply with CC41, the British government tasked local couturiers with designing most worn pieces (skirt, dress, pants, etc.) on the condition that couturiers only use utility fabrics. The programme had its benefits, as the material utilized and controlled under CC41 was of much higher quality and durability “for the first time in its history. It also benefited consumers during the war and after. Before long the society woman who pays 30 guineas for a frock will share her dress designer with the factory girl who pays 30 shillings.”[3]

Post-war, the trend in ready-to-wear continued. Historically, each decade generally had a predominant style, often based on Parisian trends. However, after WWII, Paris’s role as the major fashion centre was undermined because the cost of producing a Paris original (defined as a garment made in one of the Paris couture houses) had skyrocketed.

So couture houses all over the world started licensing out the rights for selling their high-end garments to retail outlets, which were already producing lower-priced ready-to-wear lines by the time[4].

Department store advertising fed the public’s awareness of new styles creating demand for new looks. Where pre-industrial designs lasted for years, new styles appeared every season4, starting the industry commoditization and forming new shopping behavior and fashion trends. And the rest is history.

As you can see, mass production, initially developed as a survival mechanism at the times of war, opened the door to more economical ready-to-wear lines that appeared all over Europe and the US, entirely replacing the good old made-to-measure/ on-demand at a global scale. Increasing affordability and seasonality were slowly changing social norms and attitudes around clothing. These developments further triggered the exploitation of arbitrary differences in production cost. Manufacturing was slowly moved to low-income countries with cheaper labor and resources compared to the western world; globalization made it easier to trade across borders. Fashion was slowly becoming the industry we know today.

[1] National Museum of American History (https://americanhistory.si.edu/object-project/ready-wear)

[2] https://bellatory.com/fashion-industry/Ready-to-Wear-A-Short-History-of-the-Garment-Industry

[3] https://www.racked.com/2017/8/29/16185912/austerity-wii-england-fast-fashion-high-low-hartnell

[4] am inteligencia em moda.HISTORY-AND-DEVELOPMENT-OF-FASHION